It’s worth understanding how debt cycles work – the periods of time between financial collapses – so that we can predict when the next one will come.

Governments and central banks need to know how to foresee debt crises and plot a successful course through them. For us investors, we just need to know how to take advantage.

The tell-tale signs are all there that we’re heading into the next in a long line of debt crises, with similar events in the run-up mirrored across history.

Whether the Great Depression of 1929, the Japanese bubble bursting in 1988, the dot-com crash of 2000, or the Great Recession of 2008 – all were showing symptoms of a debt crisis long before asset prices plummeted.

So, building on the theories of Ray Dalio, why are we heading into the next debt disaster, and what can we do as investors to prepare?

FYI: Stake are giving away a free US stock worth up to $100 to UK investors who sign up via the link on the Money Unshackled Offers Page. Don’t miss out!

Debt Cycles

An economy’s relationship with debt moves in predictable long-term and short-term cycles. Short-term debt cycles typically run around 12 years in length on average, with a boom-and-bust pattern of affluence and overspending, followed by austerity and bruised consumers sitting on their cash.

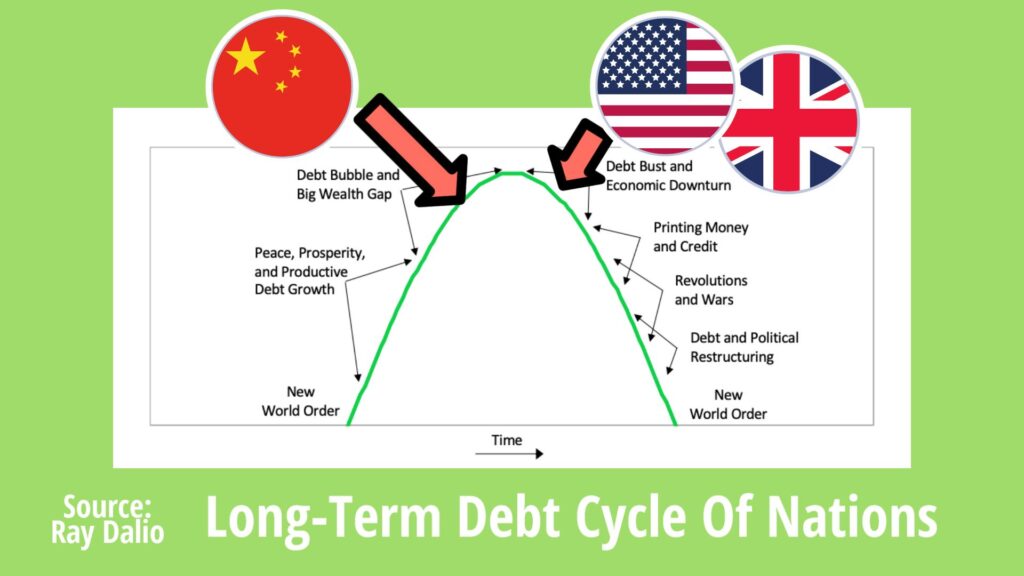

Long-term debt cycles run far longer, typically around 75 years, or could run the full length of a country’s rise to greatness through to its inevitable decline.

A country like China would sit somewhere there on the rise, with a large but reducing inequality in its population’s wealth gap, and gobbling up credit to build infrastructure and fuel growth.

Ray Dalio puts America and the UK as over the hill, America still near the top with their still booming stock market but relying more and more on money printing to get by.

Deflationary Debt Cycles

In the West, our debt cycles tend to be deflationary, which we’re covering in this article – the crisis causes investment assets to lose value and cash to become a safe haven.

On the flip side, there are inflationary debt crisis, like what happened to Germany after World War 1, where a wheelbarrow of cash was needed to buy a loaf of bread.

Credit

What we think of as money is often not money at all, but credit. You can go into a shop and buy a nice hat with a credit-card.

The shop keeper thinks you have the money, but all you’ve really given is a promise to pay the bank that money later.

When a debt crisis hits and you can’t afford to pay off that card, the truth becomes clear for all to see. That money never existed – and has now disappeared from the economy.

Short-Term Debt Cycles

Credit used correctly is a good thing, and an essential economic tool for growth.

During the good times, people use more and more credit because it makes sense to, since growth opportunities are abundant.

It doesn’t matter that they are racking up debts too, as they can be easily managed. And the banks are all-too-happy to lend money to anyone, as there is good profit to be made from doing so.

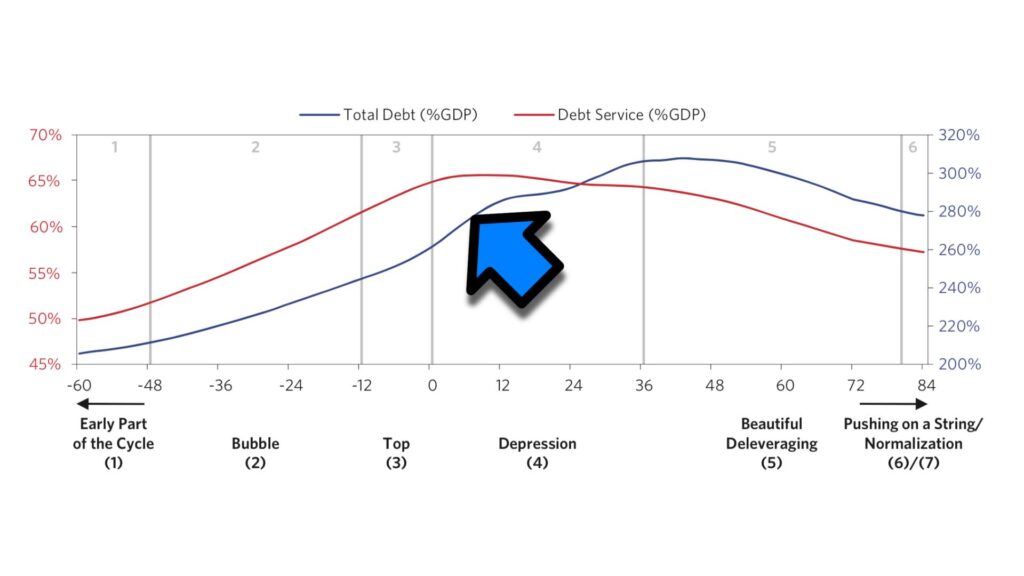

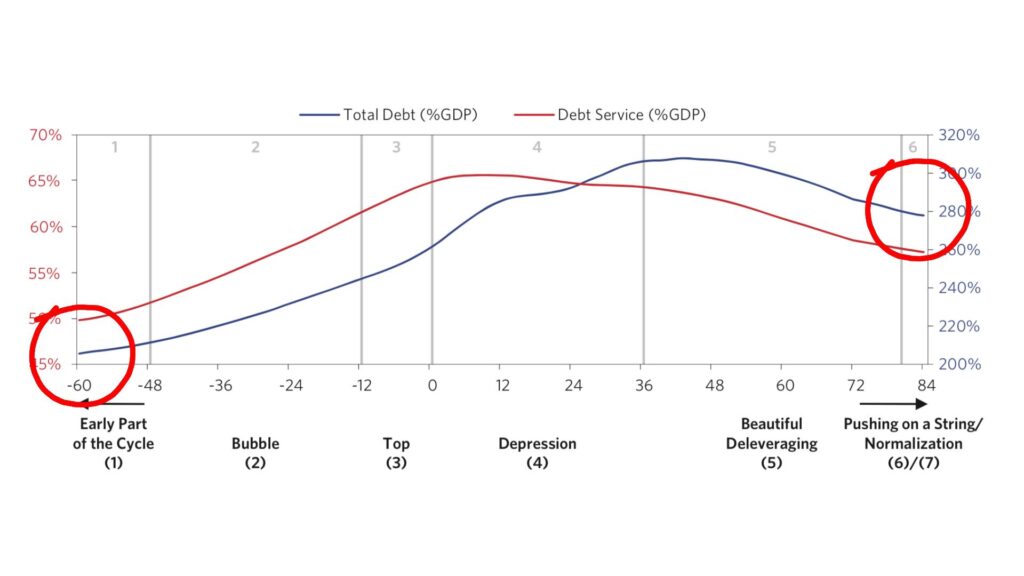

Above is what a typical short-term debt cycle looks like, taken from Ray Dalio’s book Big Debt Crises.

The bottom axis is in months and runs for 12 years, from the recovery through the bubble phase, to the inevitable decline and debt deleveraging. The red line is interest payments, but the blue line is the main one to focus on; being the total debt as a percentage of GDP.

2020 and 2021 sit in the depression phase after a good second half of the 2010s, leading up to the peak of Debt-to-GDP.

This tallies with the government’s massive printing of money during the corona-crisis.

According to debt cycle theory, we’ll soon enter the phase of the cycle when debt has to be reduced, no matter how painful, as it is unsustainable.

Note that debt typically ends a cycle higher than when it began. Several short-term cycles will balloon into a long-term cycle, starting and ending with economic catastrophes.

Why Debt Moves In Cycles: Self-Reinforcing Movements

During the good times, lending gathers momentum like a runaway train that becomes unstoppable – except for a head-on collision into something solid that knocks it off the tracks.

Lending supports spending and investment, propping up asset prices and fuelling incomes.

Bigger asset prices and incomes give banks more confidence to lend even more money, as borrowers have better collateral.

But all the while, debt is building and eventually outpaces incomes. At some point, some event will happen that triggers banks to panic, who reign in their credit lines.

Projects pause; incomes stagnate; outlooks for asset price growth look bleak; bad debts mount; and banks stop lending.

This makes the problem worse, and the debt cycle spirals downward into the end-phase.

How Debt Crises Can Be Managed

There are 5 ways to manage a debt crisis:

#1 – Austerity

Cameron and Osborne tried this in 2010 after the Recession, with limited effect.

The problem with austerity is that it is deflationary and discourages growth at the same time as the debt crisis is already doing both of those things.

It does help reduce debt, but it lowers incomes too, so can be counterproductive.

#2 – Debt Cancellations

Just cancelling the debt is not great, as the lenders lose out and this reinforces a downward spiral of deflation, but the crisis can be so severe that it might be sometimes necessary.

It’s widely believed that this needs to happen to solve the Greek debt crisis in the Eurozone, ongoing since 2009.

#3 – Slash Interest Rates

Slashing rates makes it easier for people to pay the interest on their debts, at the same time discouraging people from hoarding their money in a bank savings account.

In this way it encourages investment into the economy again.

#4 – The Magic Money Tree

The central bank just prints more money.

This only works if the country’s debts are in their own currency, but it does encourage growth and spending in the economy which really does help get things moving again.

But is this storing up a currency problem for a later day?

#5 – Raise Taxes

Raising taxes may be necessary eventually to pay for the country’s debts. But raising taxes whilst in a crisis is a big mistake.

This makes everyone poorer at a time when you need money to flow freely again.

The tax hike doesn’t even help the less-well-off, as the money is not being invested to help people, but wasted on debt payments.

However, this is the inevitable final destination for a country in ever rising net debt.

Long-Term Debt Cycles

Remember that each short-term debt cycle leaves the country a little more indebted than it was before, and after many short-term cycles the problem adds up to result in a mega crash like the Great Depression in 1929.

Many of the levers that were pulled by central banks to resolve the last several short-term crises become less effective each time.

After the 2008 recession, we lowered interest rates to almost zero. Even a decade later, rates have not recovered, so that lever cannot now be pulled again.

And the UK is now in over £2trn of debt – over 3 times higher than in 2008!

Where We Are Now In The Debt Cycle

It has been over 12 years since the start of the 2008 Credit Crunch, also now called the Great Recession.

The UK recovered: unemployment went to historic lows, the banking sector was reformed, and city centres underwent massive renovation projects.

But debt built up, and the kindling of the next debt crisis was waiting to be lit by something, and the coronavirus was more of a flamethrower than a match.

Now, we’ve seen banks pulling low LTV mortgages at the height of Covid.

We’ve seen the Bank of England base-rate slashed to 0.1%, businesses forced to shut down, and people forced to stop spending, taking credit out of the economy.

We believe we’re in the end-phase of the short-term debt cycle.

But as for the long-term cycle, 2008 might not have been the end-phase that some people assumed it was. It was a body blow, but is the knock-out punch still to come?

The levers that were pulled at the time to resolve it have been exhausted and haven’t recovered since.

Austerity has already cut back public spending as much as is politically tolerable; taxes have been raised by stealth to what we feel is the upper limit of what can be tolerated by most families; and interest rates have been slashed to the max.

Perhaps worst of all, the money printing was not rolled back at all over the last decade, and was then increased dramatically in 2020.

There is little room for manoeuvre when the next debt crisis hits. We may be just years away from a full blown 1929 style disaster.

Can Investors Take Advantage Of A Debt Crisis?

During good times of growth and demand, productive investment assets like stocks and property are favoured.

During debt crises, these assets stop being as productive, and money runs into cash and precious metals like gold and silver.

It may be too early to say, but crypto currencies like Bitcoin should logically do well during a debt crisis as well, as they act in many ways like a digital version of gold.

We’ve said before how cash itself should be given respect as an asset class in your portfolio, with perhaps a 10% allocation, and perhaps a further 10% to precious metals, and some of you may even want a small portion in crypto currencies.

During times of deflation, cash is naturally well placed to outperform, as many other assets lose value relative to it.

We’ll still hold the vast majority of our portfolios in well-diversified equities and other productive assets, but to ignore cash and precious metals entirely is to ignore the real risk of a major debt crisis coming down the road.

As long as the government keeps on printing magic money, that day keeps getting closer.

Are Debt Crises Unavoidable?

Almost. As Ray said, lending is never done perfectly and tends to be done badly.

The short-term rewards of funding faster growth with credit helps governments to justify the rising debt, and it is politically more popular to let people have easy credit than to take it away.

What politician would impose austerity and tighter restrictions on the voters during good times, before a crash had even happened?

Are you worried about the debt bubble? Tell us your take in the comments below.

Check out the MoneyUnshackled YouTube channel, with new videos released every Monday, Thursday and Saturday:

1 Comment

How ignorant you are! Virtually everything is wrong in this article. Starting from such basics like putting img from long term debt cycle and claiming it is short term.

Comments are closed for this article!